Imagine my delight to be contacted some time ago by Nicholas James of the Manchester Modernist Society and discover he had a particular interest in the sculpture of my father, Hubert Dalwood. It turned out that he was trying to trace the whereabouts of a missing piece and although unfortunately, despite searching my father's records, I couldn't help him locate it, I was doubly delighted when this initial research led him to write an entire article on my father's work.

My father undertook many public commissions in the 1950s, 60s & 70s - this was back in the day when contemporary public sculpture was usually good - and it was through these large scale (funded!) sculptures that he was able to develop many of his ideas.

As a big Modernist fan myself I was especially pleased that my dad's sculpture was being explored in this architectural context. Architecture - in many guises - was a huge influence on his work and he referenced it throughout his career.

I'm very touched to discover this new audience for my dad's work. You can read more about the ideas behind the Manchester Modernist Society and their Toastrack blog, HERE

Anyway, Nicholas has kindly allowed me to reproduce the article he wrote, so read on...........

-----------------------------------------------------------------

toastrack

Missing-Familiar

by Manchester Modernist Society

(link to original article)

My father undertook many public commissions in the 1950s, 60s & 70s - this was back in the day when contemporary public sculpture was usually good - and it was through these large scale (funded!) sculptures that he was able to develop many of his ideas.

As a big Modernist fan myself I was especially pleased that my dad's sculpture was being explored in this architectural context. Architecture - in many guises - was a huge influence on his work and he referenced it throughout his career.

I'm very touched to discover this new audience for my dad's work. You can read more about the ideas behind the Manchester Modernist Society and their Toastrack blog, HERE

Anyway, Nicholas has kindly allowed me to reproduce the article he wrote, so read on...........

-----------------------------------------------------------------

toastrack

Missing-Familiar

by Manchester Modernist Society

(link to original article)

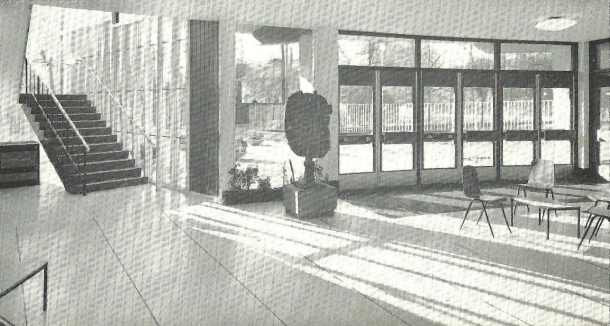

Earlier this year, Manchester Modernist Society discovered a commemorative brochure produced for the official opening ceremony of the Domestic and Trades College, performed by Princess Margaret on March 8th 1962.

The brochure outlined the college’s history, departments and staff, and offered some information on the building’s unique structure and design.

Contained within was a photograph, taken by John Williams, of the college’s dynamic entrance foyer, which featured a distinctive, cynosural object, enigmatically stood between the staircase and entrance doors.

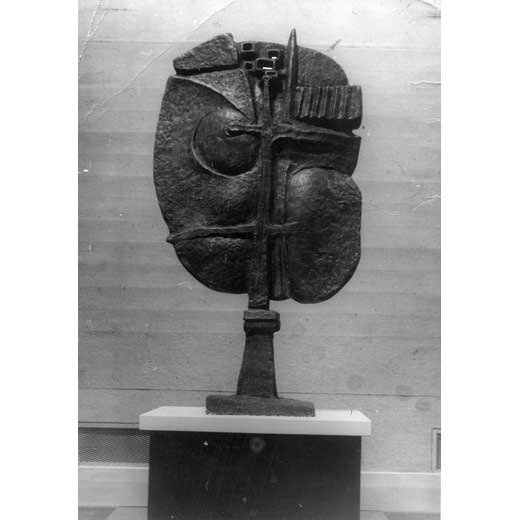

After a short investigation, this was identified as being Icon, the work of British sculptor Hubert Dalwood.

Icon (1958)

Icon (1958)

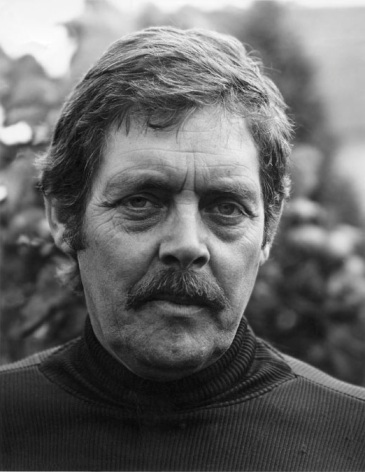

Born in Bristol in 1924 at 78 Whiteladies Road, in a suburban, lower-middle class area of 1930s semi-detached houses, Hubert Dalwood would go on to be described by critic and friend William Packer as “one of the best artists of his generation, a man who could have civilised and enlivened our cities and fired our imaginations.”

At the time of the Toastrack’s construction and opening in the late 1950s and early 60s, Dalwood’s work had won prizes and garnered acclaim in both Britain and internationally.

Throughout the 1950s, he drew upon TS Eliot’s post-war angst, describing his work as “the iconography of despair, or of defiance”. The complex relationship between sculpture and landscape, architecture and imagination forms a central theme of Dalwood’s sculpture. Many of his works appear caught in the uncertain space between object and location, between a concentration of experience of architecture and open spaces. Allusions to early civilisations and cultures, and to the body and sexuality also featured in his work.

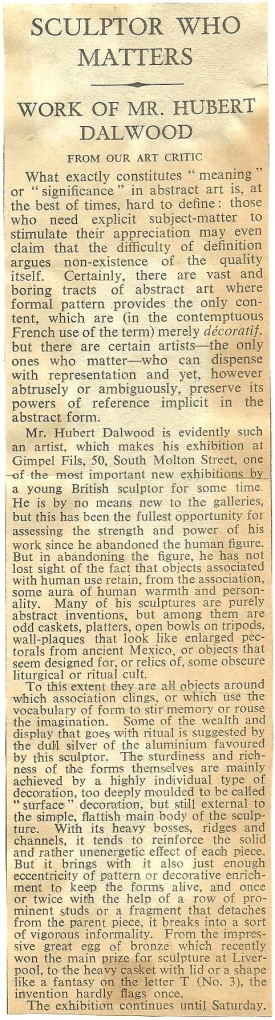

The Times, 27/01/60

The Times, 27/01/60

Architecture remained a key referent and source of fascination in Dalwood’s view of sculpture. He approached architecture and landscape as one, in terms of their relationship to each other and his subjective response to them as environments: “My attitudes are largely based on sensation… what it is like to be in a particular place, how the scale of that place relates to one, the sense of occasion and history implicit within great architecture.”

Following his first solo exhibition in August 1954 at contemporary art gallery Gimpel Fils in London, Dalwood was unanimously awarded the Gregory Fellowship in sculpture at Leeds University by a panel which includedHenry Moore and TS Eliot.

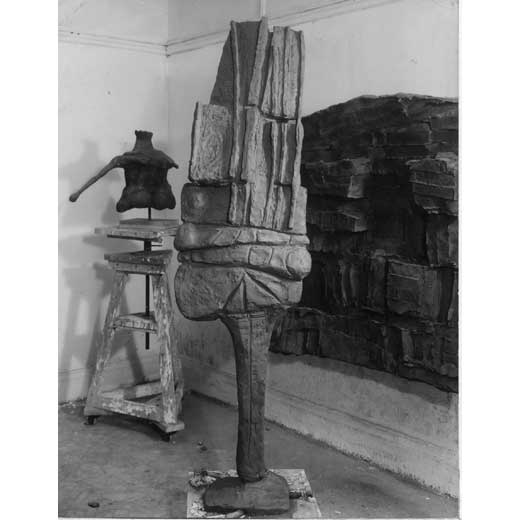

Dalwood’s Leeds studio (c. 1957)

Dalwood’s Leeds studio (c. 1957)

His three years in Leeds (1955-58) were highly influential, and connections between his sculptures from that period and the paintings of his contemporaries Alan Davie, Terry Frost and Harry Thubron – with whom he had close contact – have frequently been made by critic Norbert Lynton. It was here Dalwood “went abstract” as Lynton describes, and would go on to produce abstract objects which established him as one of the leading British sculptors of his generation.

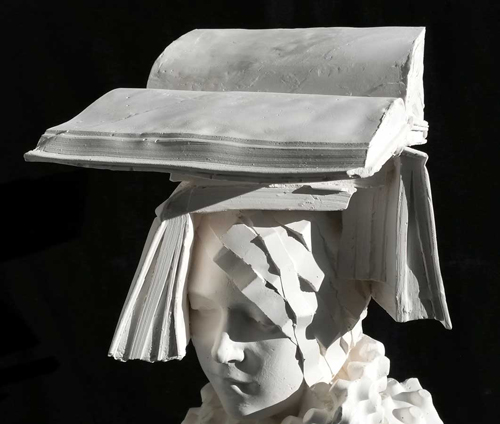

Tree (1957)

Tree (1957)

Dalwood’s Tree sculpture, a bold statement of investigation into the complex relationship between sculpture, landscape and the imagination, is cited within this context. Produced when he was 33 and later purchased by Henry Moore, Tree’s rectangular assembly of organic sections on a pedestal embodied an ambiguity of form and function that would characterise works to come.

In spring of 1956, Dalwood met with Sir Basil Spence, who was then a Visiting Professor of architecture at Leeds. Following a visit to Dalwood’s studio, Spence was so impressed by his work that he commissioned a 10 feet high sculpture for St Catherine’s church in Woodthorpe, Sheffield. The sculpture – Crucifixion with St Catherine – was completed much later in 1965.

St Michael (c. 1956)

St Michael (c. 1956)

Dalwood also submitted a figure of St Michael as a maquette to Spence for a large scheme intended for Coventry Cathedral. This proposal was turned down, but Spence went on to buy the figure for his London home, to which Dalwood became a regular guest.

1957 saw the beginning of Dalwood’s departure from figuration, and he shortly afterwards began a series of aluminium reliefs. He is one of the first British artists to cast in aluminium at that time.

“I started to think more formally and the figure became much more compact. I joined all the arms and legs up to the body and generally closed the whole thing up to make it more like lumps. This process continued until one day I thought this is nonsense, why hang the form on the peg of the figure when I am manipulating these forms against each other.”

By 1958 Dalwood’s reputation was growing, with invitations to show in a number of international exhibitions. It was at this time, as the Toastrack was being constructed, that he produced Icon.

Icon (1958)

Icon (1958)

In April of that year, critic Herbert Read visited Dalwood’s studio, particularly liking Icon, and would later write in his catalogue introduction for Dalwood’s third solo exhibition at Gimpel Fils: “The modern artist, such as Hubert Dalwood, seems determined to lead us back to the hidden sources of awe and wonder.”

Dalwood admired the organic development of form in Kurt Schwitters’ Merzbau, and the accumulative aspect of this work can be seen in Icon. Each of the sculpture’s deliberately ambiguous and abstruse symbols is evidently worked into by Dalwood’s hand, imbued with a quality of authenticity. The artist’s conception of the sculptural object rested upon a sensory dialogue between the object and the spectator. This trace of handling material, transferred from the clay into the sheen of cast aluminium, supplies Icon with an immediacy and humanism.

Icon can be seen as double-sided relief, and an implicit endeavour to find a non-figurative form of sculpture. Many of Dalwood’s works from this period – including Icon – also feature integrated, inbuilt bases, which in later work came to expand into the main sculpture.

“There is a level at which magical objects, the African thing of ritual objects, are really marvellous things, they carry a weight, a density of feeling … I made things really that I felt I could invent a ritual for. If there was a ritual… they’d carry them through the streets. There could be an involvement at this level. It’s quite nonsensical, it couldn’t happen, but it did help a little.”

The title of Icon, which Dalwood referred to as a sort of Crucifixion, signalled this most clearly. At the time of its production, he had been reading Margaret Mead’s texts on primitive sexuality, Robert Graves’ The White Goddess, and Carl Jung.

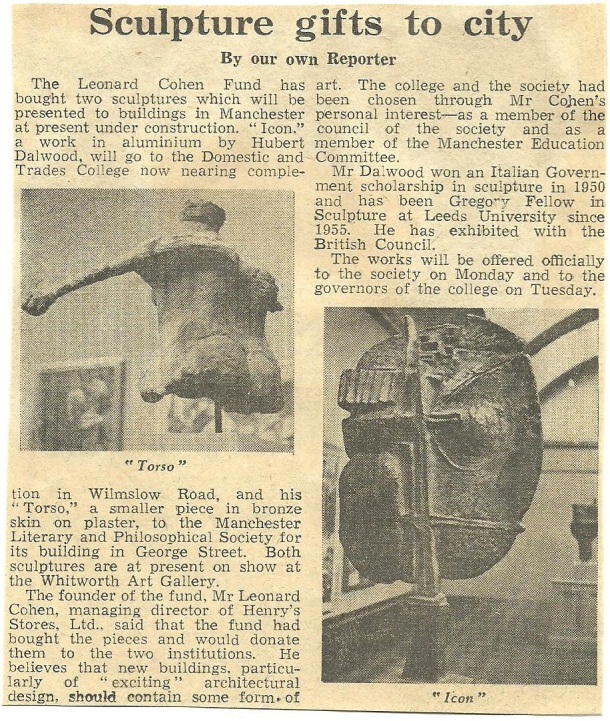

The Guardian, 04/12/59

The Guardian, 04/12/59

In 1959, Icon was presented to the Toastrack by the Leonard Cohen Fund. This particular Leonard Cohen – council member for the Manchester Literary and Philosophical Society, member of the Manchester Education Committee, and managing director of Henry’s Stores Ltd – donated the sculpture to the college, believing “new buildings, particularly of ‘exciting’ architectural design, should contain some form of art” (The Guardian, 04/12/59).

Large Object (1959)

Large Object (1959)

That year, Dalwood won First Prize for sculpture at the second John Moores Liverpool exhibition with Large Object. This work – referred to by friends as ‘The Bomb’ – can be seen as a distillation of the sense of mystery, ritual and ambiguity for which he laboured. In 1962, his work was chosen for display at the 1962 Venice Biennale, and he became internationally recognised as a major sculptor.

Benefitting from the building boom that resulted from the British post-war reconstruction and its drive for a public place for art, between 1963-4 Dalwood was commissioned by architects Beaumont & Cowling to produce a relief in his trademark aluminium for Manchester University’s Moberly Tower. This abstract articulation of ideas of growth and renewal was later to become misattributed by many as the work of sculptor Mitzi Cunliffe.

Moberly Tower Relief (1963-64)

Moberly Tower Relief (1963-64)

Moberly Tower was subsequently demolished in 2009, and Dalwood’s deracinated relief was preserved and relocated to the University of Liverpool, where it is now installed on the outside of the Science Lecture Block.

In March 1976, Dalwood was first diagnosed with systemic sclerosis, a little-know disease which prevents cell generation. He died later that year on November 2nd aged 52.

To the end he’d remained a prominent figure in the British art scene, and in 1979 a retrospective of his work was shown at the Hayward Gallery. His sculpture is in many public collections in the UK and abroad including Tate Britain, the Guggenheim and the Museum of Modern Art, New York.

Hubert Dalwood (c. 1975)

Hubert Dalwood (c. 1975)

So what became of the Toastrack’s Icon? Long-serving members of staff recall the sculpture remaining in the entrance foyer up until the beginning of the 1970s, when according to Terry Wyke’s definitive study Public Sculpture of Greater Manchester (2004), it was to “disappear”.

Casts currently exist at Leeds Art Gallery, and the Albright-Knox Art Gallery in Buffalo, New York, and it has been confirmed that neither of these are the Toastrack’s version. It is also unclear from Dalwood’s workbook, kept by him and others after his death, exactly how many Icons were cast.

Icon (1958)

Icon (1958)

Manchester Modernist Society has contacted Dalwood’s daughters Kathy and Alison, Manchester Metropolitan University Special Collections, Manchester Art Gallery, the Whitworth Art Gallery, Head of Asset Management for Manchester City Council, the Henry Moore Institute, Leeds Art Gallery, and previous surviving Deans and staff at the Toastrack – and nobody can confirm what happened to it.

There are perhaps still clues to be found, and propitious traces to be followed. If you have any information that might assist with our search, please contact: nicholas@manchestermodernistsociety.org

With enormous thanks to Kathy and Alison Dalwood for their invaluable support and guidance in the research for this article

See these posts on two recent exhibitions of my father's work

Brilliant article Kathy, how fantastic you found out about it, there was one of your fathers Sculptures at Queen's Medical Centre in Nottingham which I'm sure nobody appreciated as the base was left to rust away but I went to look at it every time I took Carole's Mother to a clinic there in the 80's and 90's

ReplyDeleteThis will be a good one for the official website too, hope there's some progress on that!!